My friendship with the great actor and director Alan Rickman did not have a particularly auspicious start.

It was March 2003 when Alan turned up at London’s Royal Court theatre, clutching an edition of the Guardian’s G2 section featuring the powerful last emails of Rachel Corrie, the American activist killed by a bulldozer in Gaza. Alan had recognised that Rachel’s voice could work brilliantly on stage, and I was commissioned to help him turn her words into a play.

But the theatrical and journalistic worlds are culturally very far apart – the former creative and thoughtful, the latter dynamic and urgent – and, as a Hollywood film star, Alan had been bitten by others in my trade. We had, shall we say, a lot of vigorous debate. Once, when I said something like: “Let’s just get on with it,” he turned to me and said, dripping with flamboyant disdain: ““Dear God, you’re such a fucking JOURNALIST.” We fought. He found me wearisome, then.

But the play we edited together, My Name is Rachel Corrie, had a greater impact than we ever imagined, with two runs at the Royal Court, a West End transfer, and productions around the world, from New York to Haifa. And on the opening night we each admitted that we couldn’t have done justice to Rachel’s words without the other. We’d been a partnership, we agreed, however crotchety. A friendship was born.

And that was lucky for me, because Alan had a great gift for friendship. He was devoted to a large number of people and would somehow always manage to visit their obscure art exhibition, or phone them at 2am when he heard they were in deep trouble, or attend their opening night even when, as we now know, he was already seriously ill. He threw dinners; he ordered every dessert on the menu if you couldn’t decide.

I once asked if a friend, a teacher from Huddersfield, could cook for him so that she could put it on her CV – “cooked for Alan Rickman” (it made sense at the time). He not only said yes, but acted as her sous-chef and rustled up a top politician and a Hollywood actor as fellow guests. When asked recently about his proudest Royal Court moment, his answer was not about him: he said it was when he took Rachel Corrie’s parents outside the front of the theatre to show them their late daughter’s name in neon lights.

Different people love Alan as an actor for different reasons – there’s the Truly Madly Deeply crowd, the Die Hard set, those who became obsessed after Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. But his role as Severus Snape in the Harry Potter movies introduced him to a whole new generation. Of course he loved Harry, but as a classical actor he did get fed up with how often it came up. While we were doing interviews for My Name Is Rachel Corrie, Alan would have a rule: they could ask just one Harry question and no more. I remember teasing him: “But Alan, you’re such a wonderful Snape, you’re so good at it!” He turned to me and said, with that languorous diction, “I know what’s required.”

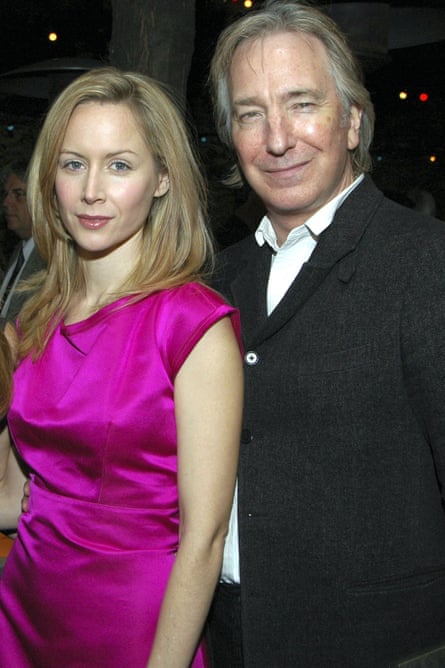

He didn’t mind being teased. His resistance to technology was a running theme (and a way of keeping some privacy in a very public life) until he finally got on email, in 2010, describing himself proudly as a “new computer geek”. From then we’d all receive witty little notes or occasionally, in my case, complaints (particularly about star ratings on Guardian reviews, which in his view made viewers lazy and reviewers power-mad). Like his partner, Rima Horton, a former Labour councillor, Alan was deeply committed to politics – a compassionate Labour man to his core.

He had been recognised everywhere he went for many years, was kind to his fan club (particularly the Arizona branch, who flew en masse to London to see My Name Is Rachel Corrie) and, as one of the Sexiest Men Alive (according to numerous polls), women would stare open-mouthed as he passed.

But the fame reached a new level with Snape. I saw this up close in April, when Alan came to the White House Correspondents’ Dinner as the Guardian’s guest; taking the short walk along a street in Washington DC from the event to a nearby whisky bar he was accosted by a succession of drunk young people, one woman sobbing loudly while begging for a selfie. (He refused all selfies – a solid rule about dignity. Non-selfie photos were fine.) He recovered quickly, and then stayed up until 3am with us all, discussing Obama, this bloody government, our hopes and dreams, the state of the world, the state of that bar, this life.