Alcohol powder

Alcohol powder or powdered alcohol or dry alcohol is a product generally made using micro-encapsulation. When reconstituted with water, alcohol (specifically ethanol) in powder form becomes an alcoholic drink. In March 2015 four product labels for specific powdered alcohol products were approved by the United States Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) which opened the doors for legal product sales. However, as of 4 January 2016, the product is not yet available for sale and legalization remains controversial due to public-health and other concerns.[1] Researchers have expressed concern that, should the product go into production, increases in alcohol misuse, alcohol use disorder, and associated physical harm to its consumers could occur above what has been historically associated with liquid alcohol alone. [citation needed]

History[edit]

Invention[edit]

In 1966 Sato Foods Industries Co., Ltd. invented alcohol pulverization. Sato is a food additives and seasoning manufacturer in Aichi Prefecture in Japan. (ja:佐藤食品工業 (愛知県))[2][3] A year later, in 1967, Sato began production and sales of various kinds of "high content alcohol powder Alcock" ("高含度アルコール粉末「アルコック」").[3]

On 15 January 1974, a practical manufacturing process for alcohol powder was patented by Sato.[4][5][6][7] Sato has patented the process in 17 countries around the world.[8][9][10]

In the 1970s Sato began promoting powdered alcohol in the United States. Test sales began in 1977 under the trade name "SureShot".[11][12] The product "Palcohol" was announced for future release in the U.S. in 2015.

Customer base[edit]

Officially, Sato says that its products are for business use only, for example for the use of food-processing industries or food-and-drink businesses (e.g. restaurant, café, sweets shop, bakery shop, etc.). Mainly, its products are to be used as food additives. Other than purposes for test sale, research, etc., it has never been sold for eating or drinking, including personal use or home use.[9][13]

In June 1982, Sato started production and sales for the drinking powdered alcohol, as test case. Its name is "powdered cocktail Alcock-Light cocktail" ("粉末カクテル 'アルコック・ライトカクテル' ").[3][14] At least, during some years, it seems that had continued to test sales.[15][16]

Public health concerns[edit]

Powdered alcohol would generally share the health risks that are associated with traditional liquid alcohol consumption, although there may be some differences in its effects. Examples include differences in consumption potency, differences in characteristics for storage, concealability, portability, lack of familiarity, and potentially novel delivery methods. Excessive consumption of alcohol, powdered or liquid, can result in acute overdose, intoxication-related accidental injury, compromised judgment, and longer-term negative health consequences including liver disease, cancer, and physiologic dependence.[17]

Consideration for retailers[edit]

As with the public health concerns, the following concerns have been posed but data are not yet available to prove or disprove them. Because of the unique characteristics of powdered alcohol, introduction in the U.S. could raise significant concerns from alcohol retailers as it will raise the awareness of their customers health and well as a major priority. including such as restaurants, bars, and sporting venues,[18] including:

- Availability of powdered alcohol could negatively affect retailers' economic interests as customers might now have the ability to purchase less relatively expensive and safer alcohol from those businesses by augmenting their purchased liquid alcohol drinks with cheaper powdered alcohol mixtures purchased elsewhere.

- Use of powdered alcohol by customers could increase responsibility of these businesses' by increasing the accuracy and abilities to monitor their customers' alcohol consumption - which they are legally required to do to try to prevent the consumption of alcohol by intoxicated or under-age customers. This could hold them at a greater responsibility out of concern of civil-liability lawsuits (because retailers are held liable for alcohol-attributable harms caused by customers who should not have been served alcohol).

Production process[edit]

→:air (in=hot, out=cool)

'•':sprayed mixture

Black=dextrin film

Red--=alcohol mixture

Powdered alcohol is made by a process called micro-encapsulation.

An auxiliary material for a capsule may be any readily water-soluble substance (e.g. carbohydrate such as dextrins (starch hydrolyzate), protein such as gelatin). For powdered alcohol, maltodextrin (a type of dextrin) was chosen.

For the process to encapsulate, a method called spray drying was selected.[14][19]

In this process, a mixture of dextrin and alcohol is subjected to simultaneous spraying and heating. The spraying converts the liquid to small drops (up to several hundred μm (micrometers) in diameter), and the heat causes the hydrous dextrin to form a film. When the film dries, the drop becomes a microcapsule containing alcohol and dextrin.

Before and after drying, comparing the amounts of water and alcohol, about 90% of water is removed and about 10% of ethyl alcohol is lost.[15] One of the reasons which are considered, is the following.

In mixtures such as this, the speed of molecule movement is dependent on molecule size and carbohydrate (in this case, maltodextrin) concentration. Water, the smallest molecule in the mixture, is able to move and evaporate fastest. In higher concentration, by decreasing water, water molecules can move much faster. After the film formed it is less permeable to larger molecules than water. By the time the film is completed, water has evaporated enough. This phenomenon is called "selective diffusion."[20]

In general, after sprayed, encapsulation for each drop is completed within about 0.1 second from the very beginning of the process. There is no time for the internal convection in each drop or capsule to occur.[15]

Ultimately, large amounts of microcapsules have been produced. These become the powdery matter called powdered alcohol or alcohol powder. According to Sato's web page, powdered alcohol contains 30.5% ethyl alcohol by volume in the state of powder.[10]

In addition to the mixture before drying, if necessary, other additives (e.g. extract, sweetener, spices, coloring matter, etc.) may be added.

As a result, alcohol powder can be said to be an alcoholic beverage that is "dry". For example, a "dry martini" made from alcohol powder may be referred to as a "dry dry martini" or "dried dry martini".[11]

In the production of alcoholic powder production, other drying methods are not used. [citation needed]

For drying foods, there are other methods.[21]

Typically, when considering the quality of a powdered product such as coffee, freeze drying seems to be better than spray drying, but this does not apply to alcohol powder production. In fact, "freeze-dried beer spice" was made by university students for their research. Carbon dioxide, water and alcohol have all been lost.[22]

Due to the volatility of alcohol, relatively higher than water, time-consuming methods, such as freeze drying, should not be used. By selective diffusion, loss of alcohol is relatively small.

Non-commercial production[edit]

In 2014, an article on the website PopSci.com published instructions on how to make pulverized alcohol easily, through a simple mixture of alcohol and dextrin.[23]

In this method, the powder is not encapsulated, and also not yet fully dried. Consequently, alcohol continues to evaporate from it very rapidly.

Due to flaws in the powdered alcohol produced by this method, this form of powdered alcohol was said to be unsuitable for drinking, carrying, or preserving.

Any production of powdered alcohol without a license is illegal in Japan, even if it is only for personal use, according to the Liquor Tax Act of Japan.

Market[edit]

Sale in Japan[edit]

The alcoholic beverage industry in Japan is large. For example, in fiscal year 2013, Suntory, one of the country's largest beverage companies, recorded sales of 570.7 billion yen (about US$4.7 billion) in alcoholic beverages, excluding wine.[24] Currently, the sales revenue from powdered alcohol has been too small to affect the sales of liquid-alcohol companies. Additionally, powdered alcohol's market share is currently too small to be considered as a statistical item in Japanese tax reports.[25]

Powdered alcohol is found in some mass production foods, used in small amounts (as are other additives).

Promotion in the United States[edit]

In 1977, the Associated Press delivered the first news story in the United States about powdered alcohol, which was then an unprecedented product. Investors were quoted as saying that they "hope[d] to revolutionize the liquor business with a product that's easy to carry, cheap and potent". A test sale of powdered alcohol, called "SureShot", was done in the United States.[11][12][26]

Chemical properties[edit]

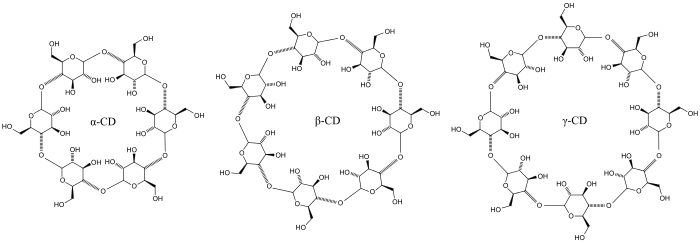

According to food chemist Udo Pollmer of the European Institute of Food and Nutrition Sciences in Munich, alcohol can be absorbed in cyclodextrins, a synthetic carbohydrate derivative. In this way, encapsuled in small capsules, the fluid can be handled as a powder. The cyclodextrins can absorb an estimated 60 percent of their own weight in alcohol.[27] A US patent was registered for the process as early as 1974.[28]

Routes of administration[edit]

- Reconstituted: Alcohol powder can be added to water to make an alcoholic beverage.[29]

- Nebulizer: Alcohol powder produced through molecular encapsulation with cyclodextrin can be used with a nebulizer[30] though this could be dangerous.

Prevalence and legal status[edit]

This article needs to be updated. (February 2016) |

Australia[edit]

Powdered alcohol is illegal in the state of Victoria, as of 1 July 2015.[31] As of the Liquor (Undesirable Liquor Product - Powdered Alcohol) Amendment Regulation 2018, made under the Liquor Act 1992, Powdered Alcohol in Queensland was banned and pronounced illegal.[32] The NSW Government also recognises powdered alcohol an undesirable product under the Liquor Regulation Act 2018.[33]

Germany[edit]

In 2005, a product called Subyou was reportedly distributed from Germany on the Internet.

The product was available in four flavors and packed in 65-gram, or possibly 100-gram, sachets. When mixed with 0.25 liters of water, it created a drink with 4.8% alcohol. It was assumed that a German producer manufactured the alcopop powder based on imported raw alcohol powder from the U.S.[34]

Later, Subyou disappeared and its website: 'subyou.de', was taken down.[35]

Japan[edit]

The Japanese Liquor Tax Act (ja:酒税法) amendment of April 1981[36][26] classifies powdered alcohol as an alcoholic beverage. In the production of powdered alcohol some non-alcoholic ingredients are added which is similar to some liqueurs. Nonetheless, powdered alcohol became a separate category of alcoholic beverages.

In May 1981, Sato received the first license to produce alcohol powder commercially. In Japan, powdered alcohol is officially called, funmatsu-shu (ja:粉末酒, lit. 'powdered-alcoholic beverage').[3] Powdered alcohol is defined by law as a "powdery substance that can be dissolved, and can make a beverage containing 1% or more alcohol by volume".[37]

Before the 1981 amendment, powdered alcohol was outside the scope of Liquor Tax, as it is not a liquid.[14]

Netherlands[edit]

In 2007, four food technology students in the Netherlands invented a powdered alcohol product called "Booz2go".[38] They claimed that when mixed with water, the powder would produce a bubbly, lime-colored and lime-flavored drink, with 3% alcohol. When put into commercial production, it was expected to sell for €1.50 (approx. US$1.60) for a 20 gram sachet.

The product's creators and marketers – Harm van Elderen, Martyn van Nierop, and others at Helicon Vocational Institute in Boxtel – claimed to be aiming at the youth market. They compared the drink to alcopops like Bacardi Breezer and said they expected the relatively low alcohol content would be popular with the young segment.

Because of complexities in Dutch laws, powdered alcohol like Booz2Go would not be subject to the Alcohol and Horeca Code, because it is not literally an alcoholic drink. This means that anybody of any age could buy it legally. However, when dissolved in water, it would be subject to the Code, according to Director Wim van Dalen of the Dutch National Foundation for Alcohol Prevention. Von Dalen commented that while he generally did not support new alcoholic drinks, he doubted the powder would become attractive. A spokesman of the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport said they would not undertake any actions against the product, but added that the label would have to contain a warning about any health risks for the consumer, in accordance with other laws.[39]

In 2014, Booz2go is not yet commercially available.[35]

Russia[edit]

Russia had plans to ban powdered alcohol in 2016.[40]

According to one Russian news site, in 2009, a Professor at Saint Petersburg Technological University named Yevgeny Moskalev invented and patented a method of creating alcohol powder. This method could make alcohol powder from any kind of alcoholic beverage.[41]

The method was tested on 96% spirit vodka. In this method, melted wax (stearic acid) is stirred, and the alcoholic drink is poured in. The solution dissipates and becomes drops containing alcohol and wax. The drops that solidify constitute alcohol powder.

United States[edit]

In 2008, Pulver Spirits began developing a line of alcohol powder products to be marketed in the United States. The marketing was reportedly intended to be in full compliance with alcohol regulations and targeted at adults of legal drinking age.[42]

In Spring 2014, the Arizona-based company Lipsmark LLC announced that it would start marketing powdered alcohol under the name "Palcohol", a portmanteau of powder + alcohol.[43] This caused considerable controversy, after the product was approved by the TTB for sale. This approval was later attributed to a "labeling error", and the manufacturer surrendered the approvals.[44]

In March, 2015, the U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) approved four powdered alcohol products with the brand name "Palcohol" for sale in the U.S.[45] Under the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution, state and territory governments also have substantial regulatory powers over "intoxicating liquors", especially regarding retail sales and sales to minors.[46] Shortly after the TTB approval was announced, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) responded to inaccurate reports implying that it had approved powdered alcohol as being safe. The FDA clarified that its role was to evaluate the nonalcoholic ingredients and that based on its evaluation of specific powdered alcohol products it had no legal basis to block their entry into the U.S. market.[47]

In 2014, Ohio state legislators introduced legislation that would ban Palcohol and all other powdered alcohol.[48] The following year, Iowa state legislators followed suit.[49]

Sales were legalized in Colorado in March 2015.[50]

On 25 March 2015, alcohol wholesalers and distributors in the state of Maryland announced an agreement to voluntarily ban the distribution and sale of powdered alcohol.[51] Concerns included the potential for misuse by minors, the ease of using the powder to bring alcohol into public events or to spike drinks, and the potential to snort the powder. At the same time, a bill to ban Palcohol for one year was under consideration in the Maryland House of Delegates.

In September 2015, the New Hampshire Liquor Commission banned the sale of Palcohol.[52]

By November 2015, most states had introduced legislation and laws to regulate or ban powdered alcohol. Twenty-seven have banned powdered alcohol, 2 more have placed temporary 1-year bans on the product and 3 have included powdered alcohol under their statutory definitions of alcohol meaning that it is covered by existing alcohol regulations.[53][needs update]

United Kingdom[edit]

The legal status of powdered alcohol in United Kingdom is uncertain, although parliament saw no dangers from the sale of powdered alcohol, aside from the loss of tax revenue.[54] In a January 2015 answer to a parliamentary question, Lord Bates wrote "The Government is aware of powdered alcohol from media reports and the banning of the product in five states of the United States of America. The Government is aware of powdered alcohol being marketed and made available in the coming years to buy in England and Wales."[55]

References and annotation[edit]

- ^ "Powdered Alcohol: An Encapsulation" (PDF). NABCA Research. National Alcohol Beverage Control Association. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^

Corporate Information Sato Foods Industries Co., Ltd. (佐藤食品工業株式会社, Sato Shokuhin Kogyo Kabusihigaisha) (pronounced by Google Translate of "佐藤 食品 工業" ("Satō Shokuhin Kogyō")).

– About the official name in Japanese language of Sato Foods Industries Co. Ltd, it takes an attention there are comparatively many companies that has similar name "Sato so-and-so", because "Sato" is most common surname of Japanese people. This company exists in Komaki-shi (-city) (ja:小牧市), Aichi-ken (-pref.) (ja:愛知県), Japan.

– Its founder and top manager 佐藤 仁一 (SATO, Jinichi ("SATŌ, Jin'ichi"); Mr.) is also an engineer, graduated from Sch. of Eng. of Kyoto Imperial University (京都帝国大学) (Later, Kyoto University (ja:京都大学)) in 1947, he and his team invented the powdered alcohol. - ^ a b c d

有価証券報告書(Financial statement) (in Japanese) Sato Foods Industries Co., Ltd. (Japan)

– Original sentences of powdered alcohol-related parts in Japanese language excerpted from "【沿革】" ("History") in financial statement (ja:有価証券報告書) without quarterly finance report (ja:四半期報告書)... - ^ US3786159 A, Kurutsu T, Sato J (Sato Shokuhin Kogyo KK), Process of manufacturing alcohol containing solid matter, filed 13 December 1971, pub. 15 January 1974, also published CA958274A1, DE2162045A1, DE2162045B2, DE2162045C3. (Google patents)

- ^ Patents search-key words="Sato Shokuhin Kokgyo" (Google patents)

- ^ US3795747 A, Mitchell W, Seidel W (Gen Foods Corp), Alcohol-containing powder, filed 31 March 1972, pub. 5 March 1974, also pub. CA1015296A1, DE2315672A1. (Google patents)

- ^ Patents search-key words=alcohol powder "alcoholic beverage" (Google patents)

- ^ "What Is the Big Deal about Powdered Alcohol?", scientificamerican.com, 25 April 2014.

- ^ a b "米国で認可の「粉末アルコール」、日本にはすでに存在していた" ("U.S. approved "Alcohol powder", in Japan already exists") (in Japanese), 日刊! (Daily SPA!, a daily news site), 24 April 2014. (Japan) (ja:SPA!)

- ^ a b Powdered alcohol, Sato Foods Industries Co., Ltd. (Japan)

- ^ a b c Examples of news of "SureShot" (Sato's product for test sales in US) in 1977 & 1978...

- Photo of "SureShot" Archived 20 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, bevlaw.com, Lehrman Beverage Law, PLLC

- "Dry martini? Powdered booze is punch in a pouch" Archived 20 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine(PDF) (AP delivery), The Seattle Times, 8 June 1977.

- "Investors see $$$ in powdered booze" The Bulletin, 8 June 1977. (Google news)

- "Powdered Booze Is Next Thing" Observer–Reporter, 6 June 1977. (Google news)

- "Powdered martini in the bag" Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, 11 June 1977. (Google news)

- "Want instant cocktail or beer? Now you can go take a powder" The Milwaukee Journal, 30 January 1978. (Google news)

- ^ a b News search-key words=powdered alcohol powder (Google news)

- ^ "粉末酒" ("Powdered alcohol") Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) (in Japanese), "お酒のはなし" ("The Story of Sake") (No.7, 30 March 2005), P.6, National Research Institute of Brewing (NRIB) (Japan) (ja:酒類総合研究所)

- ^ a b c 佐藤 仁一 (SATO, Jinichi) (佐藤食品 工業(株), Sato Foods Industries (Co., Ltd.)) "粉末酒 (含アルコール粉末)" ("powdered alcohol (Alcohol-containing powder)") (PDF) (in Japanese) 日本釀造協會雜誌 (BSJ Journal), Vol. 77 (1982) No. 8, pp. 498–502, 日本釀造 協会 (Brewing Society of Japan (BSJ)).

- ^ a b c d

佐藤 仁一 (SATO, Jinichi), 栗栖 俊郎 (KURUSU, Toshirou) (佐藤食品工業(株), Sato Foods Industries (Co., Ltd.)) "含アルコール粉末" ("Alcohol-containing powder") (PDF) (in Japanese) 日本食品工業学会誌 (JSFIS Journal), Vol. 33 (1986) No. 2, pp. 161–165, 日本食品工業学会 (The Japanese Society for Food Industrial Science (JSFIS)) (Later, The Japanese Society for Food Science and Technology (日本食品科学 工学会)).

– Electron micrographs of micro-capsules of powdered alcohol can be seen. - ^ "粉末酒アルコック・ライトカクテル新タイプギフトセット (佐藤食品工業)" ("Powdered alcohol 'Alcock-Light Cocktail' New type gift set (Sato Foods Industries)") (in Japanese), ニューフードインダストリー ("New Food Industry"), 1983 Vol.25 No.7 (July 1983), P.78, 株式会社食品資材研究会 (Food Materials Research Society Inc.) (Japan)

- ^ "Liquid Alcohol and Public Health". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Naimi, Timothy S; Mosher, James F. (14 July 2015). "Powdered Alcohol Products: New Challenge in an Era of Needed Regulation". JAMA. 314 (2): 119–120. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6450. PMID 26075642.

- ^ "We established the term SprayDry in 1942 and it became a registered trademark in 1951." SprayDry Nozzles: Overviews, Spraying Systems Co. (spray drying tech.-related co., in U.S.) – Depending on the notation may become trademark infringement.

- ^ L. C. MENTING and B. HOOGSTAD "Volatiles Retention During the Drying of Aqueous Carbohydrate Solutions" Journal of Food Science Vol.32 Issue 1 (January 1967), pp. 87–90, Institute of Food Technologists (United States)

- ^

Technologies Amano Foods (Alias of Amano Jitsugyo Co., Ltd. (ja:天野実業株式会社), a dried foods manufacturer) (Japan)

– explanations of practical drying foods process with photos. - ^ Purdue students brew up idea for freeze-dried beer spice Purdue News, purdue.edu Purdue University, 20 May 2002.

- ^ "HOW TO MAKE POWDERED BOOZE", popsci.com (Popular Science), 22 April 2014.

- ^ サントリーグループの概要 (Suntory group overview) (in Japanese) 2013FY, Suntory Holdings Limited (サントリーホールディングス株式会社). (Japan).

- ^ 統計情報・各種情報 (Statistical Information and various kinds of information) (in Japanese), 酒税行政関連情報(お酒に関する情報) (Information about the liquor tax administration-related (Information about alcoholic beverages)), 国税庁 (National Tax Agency) (Japan)

- ^ a b

"Japanese Ready Powdered Booze" Reading Eagle, 12 March 1981. (Google news)

– Report about Law to amend the part of the Liquor Tax Act (March 1981, Japan), and - ^ Alcohol powder: Alcopops from a bag Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Westdeutsche Zeitung, 28 October 2004 (German)

- ^ Preparation of an Alcohol Containing Powder, General Foods Corporation 31 March 1972

- ^ "Powdered Alcohol Coming to the US". IFLScience. 21 April 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ Le, V. N.; Leterme, P.; Gayot, A.; Flament, M. P. (2006). "Aerosolization potential of cyclodextrins—influence of the operating conditions". PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology / PDA. 60 (5): 314–322. PMID 17089700.

- ^ Willingham, Richard (1 July 2015). "Powdered alcohol banned in Victoria but national ban will not be enforced". The Age. Fairfax. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ "Liquor (Undesirable Liquor Product—Powdered Alcohol) Amendment Regulation 2018". Legislation of Queensland. 2018. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Liquor Regulation Act 2018. NSW Legislation".

- ^ "Statt Alcopops droht Sucht in Tüten". Die Tageszeitung (in German). 10 November 2004. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009.

- ^ a b "The Surprising History of Making Alcohol a Powdered Substance", Smithsonian.com, 7 May 2014.

- ^ 酒税法の一部を改正する法律 [昭和56・3・31・法律5号] (昭和56年4月1日 施行] (in Japanese) (Law to amend the part of the Liquor Tax Act [Act No.5 March 31, 1981]) (1 April 1981 enforcement) (Japan)

- ^ "溶解してアルコール分1度以上の飲料とすることができる粉末状のもの" (in Japanese) (Original sentence of definition of powdered alcohol by law of Japan), 酒類の定義 (Definition of alcoholic beverage), National Tax Agency (Japan) (ja:国税庁)

- ^ Just add water – students invent alcohol powder Reuters, 6 June 2007

- ^ Students make alcohol powder, Het Parool, 25 May 2007 (Dutch)

- ^ "В России запретят "сухой алкоголь"". Коммерсант. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Now Vodka Can Be Consumed as Food (in English) pravda.ru, 27 November 2009. (Russia)

- ^ Amara, Audrey (4 July 2008). "Alcohol Powder Starts Flowing". Science 2.0. ION Publications LLC. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ bevlaw.com. "Powdered Alcohol". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Stampler, Laura; Alexandra Sifferlin (22 April 2014). "Feds: Powdered Alcohol Approved in 'Error'". TIME. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ ABC News. "Everything You Want to Know About Palcohol, the Powdered Alcohol Approved by Feds". ABC News. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "Consumer Corner: TTB's Responsibilities - What We Do". United States Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "FDA Clarifies its Role on "Palcohol"". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Walsworth, Jack (22 July 2014). "Powdered alcohol? Ohio may ban it". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Lynch, James (2 February 2015). "Iowa Legislature considers ban on powdered alcohol sales". The Gazette (Cedar Rapids). Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Colorado Allows Sales of Powdered Alcohol". NPR.org.

- ^ "Retailers, Distributors Agree To Powdered Al – WBAL Radio 1090 AM". Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "Powdered alcohol banned in New Hampshire", seacoastonline.com, 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Powdered Alcohol 2015 Legislation". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "When will powdered alcohol (Palcohol) be available in the UK?". Alcohol Emporium. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "Alcoholic Drinks:Written question – HL3819". UK Parliament. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

Further reading[edit]

- "Powdered alcohol approved for sale, bill filed to keep it out of Texas". KVUE. 12 March 2015. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Legislative Activity – Dangerous Products", Alcohol Justice.